My very first bowl of ramen (the fresh stuff, not the packaged instant kind) was about five years ago in Toronto. My super cool cousin Alan, repatriated after a brief sojourn in Japan and well aware of my penchant for Asian food, was eager to introduce me to the dish that was all the rage in that gastro-centric island. The only ramen restaurant, to our knowledge, that existed in Toronto at the time was a little Korean-run spot called Kenzo, located in an unassuming blink-and-you’ll miss it strip mall near Yonge and Steeles (just south of glorious Centrepoint mall, for those of you, like us, who lived in the area). One bite and I was converted. But it certainly wasn’t easy convincing friends that it was worth trekking north of the subway line’s end just for a bowl of noodles. For awhile, despite the rising popularity of ramen in other food-savvy North American cities like New York, Vancouver and San Francisco, that first outpost of Kenzo remained the only spot in Toronto to get your slurp on. Within the past year though, and the past couple months in particular, our ramen landscape has drastically altered, with a surge of new spots popping up all over downtown. Indeed, we’re (finally) in the midst of ramen mania (or ramenia, for the portmanteau lovers out there).

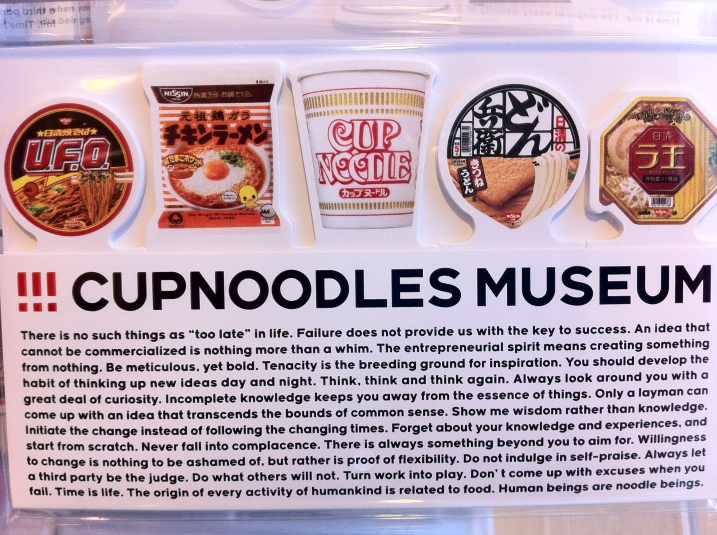

In Japan, ramen is not just the newest food trend, but a fundamental element of contemporary food culture – consumed by everyone, obsession to many, and for some, a way of life. Across the country, there are over 4000 shops turning out bowls of these beloved brothy noodles, which means an immense range of style and quality. People wait in hour+ lines to try the work of a legendary master or of a new innovator. There are scores of blogs, both Japanese and English, dedicated to documenting the best ramen shops, along with ramen magazines, manga, tv shows etc. There is even a ramen museum (not to be confused with the Cupnoodle Museum of my inaugural post) where visitors can learn about the history of the dish and sample bowls from some of the country’s most famous purveyors (I obviously made a special trip there while in Japan, where I had my first ever encounter with ramen coma). And of course, ramen movies, like the1985 critically acclaimed Tampopo, a hilarious and extremely well-made “ramen western” which you should totally watch. I know it looks hokey, and it is, but trust me – watch it.

As for the composition of the dish itself, preparations can vary immensely, particularly between regions, but there are generally four basic elements: the broth, the tare, the noodles, and the toppings. The broth is usually pork and/or chicken (+ vegetables), though some use seafood, with each shop developing its own blend. As the element that gives the dish most of its body and flavour, it’s generally the battleground on which ramen shops compete. The tare is like a strong seasoning sauce, spooned into the bottom of the bowl to later mingle with the broth. There are three basic varieties, with the tare being the factor to determines the ramen’s type: shoyu, which is soy sauce based; miso, the notorious fermented bean paste; and shio, a salt-based sauce that also contains some seafood and seaweed essence. To make it all more confusing, there is a fourth type of ramen, tonkotsu, a rich, creamy pork bone broth which has tons of flavour in itself, and may or may not be mixed with tare. Noodles can be thin or thick, curly or straight, but are usually wheat-based alkaline noodles. For me, the noodles are as important as the broth – must be chewy! Serious shops use fresh handmade noodles rather than packaged stuff. Finally, the toppings usually include roast pork (belly or shoulder), a boiled egg, and some simple vegetables like bean sprouts, mushrooms, and bamboo shoots.

Unsurprisingly, there are many variations on these basic elements, with lots of interesting, sometimes funny, innovations and trends. Tsukemen, for example, is an extremely popular style where broth and noodles are served separately. The broth is more concentrated than that of a typical ramen and serves as a dipping sauce for the noodles (inspired by the traditional way of eating soba). Then there’s a shop called Jiro ramen which has become insanely popular in Japan for just loading on heaping tons of toppings.

There are even places using ice cream in their ramen, like this one with an actual ice cream cone in the bowl, or this chilled soy-milk broth ramen with chili oil ice cream and chicken. Eek. While Toronto’s not quite at that stage yet, we’ve finally got a respectable number of ramen shops slinging their own versions, including some creative bowls in the mix. Without much further ado, here are all the spots to score yourself some slurpy goodness:

(1) Santouka (Dundas and Church)

A Hokkaido-based ramen shop with several locations worldwide and many devout followers. Their signature, shio ramen, is topped with a pretty pickled plum and is just plain incredible. Try it. They also serve tsukemen, the dipping ramen, which I’ll have to go back for.

(2) Ramen Raijin (Yonge and Gerrard)

From the owner of some successful Vancouver ramen shops, Raijin’s the newest kid on the block. They were in soft-opening for awhile but now serving their full menu as of yesterday. Their ramen is great and they have the most diverse menu by far, including a vegetarian option, chicken broth ramen (which are clear and light – they’re pretty salty too but you can ask them to adjust when you order) and tsukemen. Their most unique dish is a bamboo charcoal dark miso ramen, which actually contains food-grade charcoal powder (apparently considered a toxin cleanser). Also some tasty sounding sides like pork buns and Japanese poutine. In addition to their food, one of their biggest draws is that the restaurant is huge compared to other places, meaning you probably won’t have to wait long in line, if at all. It could also accomodate large groups.

(3) Sansotei (Dundas and University)

Their signature is the pork-bone broth tonkotsu ramen and it is definitely something to write home about (if you’re from a food-obsessed family like mine I guess). I literally drank every last drop. They were getting some flack from customers about not having the chewiest noodles to match their amazing broth so they actually listened – they upgraded to Japanese quality noodles and are now offering customers a choice of noodle type.

(4) Kinton Ramen (Baldwin Village)

From the people who brought you Guu, it’s the most fun and lively of all the ramen shops (as expected from Guu). Their noodles, made in house, are excellent and their pork belly is serious business. Options include a cheese ramen, with swiss cheese and basil toppings (I haven’t tried but sounds good) as well as a corn kernels topping (yum). On Wednesday evenings, they do a limited amount chicken ramen.

(5) Kenzo (Spadina and Bloor; Bay and Dundas; Yonge and Wellesley; Yonge and Sheppard)

The owners of Toronto’s first ramen shop at Yonge and Steeles (now under different ownership) have since expanded to four locations throughout the city. While it’s not the best bowl of ramen ever – their broth isn’t the richest nor noodles the chewiest – it’s stil really tasty food that hits the spot. I’ve been there a handful of times and always order the King of Kings ramen. It’s good stuff.

(6) Momofuku Noodle Bar (Richmond and University)

From the infamous and innovative David Chang. There’s only one bowl of ramen on the menu, and it’s made with bacon. Not traditional, tastes great.

(7) A-OK Foods (Queen and Shaw)

This place just opened last week so I have yet to try it, but it’s from the people behind Yours Truly, who used to serve the tastiest snack menu (R.I.P.), so hopes are high. Amongst other snacks, they have a shio ramen and a tsukemen sichuan ramen (mmm, sounds good). I’m gonna guess they’re both untraditional.

(8) Ajisen (Spadina and Dundas; Yonge and Empress)

Big menu. Don’t have much to say as I just don’t really like this place.

(9) Ramen and Izakaya Ryoji (College and Montrose)

Set to open sometime before Christmas, Ryoji, with several branches in Okinawa, promises to bring us some Okinawan style ramen.

Go get your slurp on.